End of year review

2022 reflections

It is just over a year since I posted my predictions for the travel industry in 2022, and the time has come to look back on the year with the benefit of hindsight and to speculate about what might happen in 2023.

Demand

My first confident prediction was that there would be no shortage of underlying demand and that the travel restrictions which had been introduced in the face of the Omicron variant would be short-lived. I expected Easter to be strong and that the summer season would be the first “normal” season for three years. I even thought there was a chance that pent-up demand could make it one of the strongest in years.

I was certainly correct that omicron-related travel restrictions would be short-lived, with the notable exception of China. In the UK, even the requirement for travel tests was gone by the 11th February. Traffic rebounded quickly, with European passenger volumes at Heathrow hitting 80% of pre-COVID levels in April and North American traffic doing the same a month later (see chart below). The region classified as “Latin America” in Heathrow’s numbers includes the Caribbean and was above 2019 volume levels all year, thanks to Virgin Atlantic consolidating all its routes at Heathrow. The only region which was not hitting around 90% of 2019 levels by the end of the year was Asia / Pacific, thanks to continued travel restrictions in Asia and the impact of the war in Ukraine, with European carriers being unable to over-fly Russian airspace.

Source: Heathrow, GridPoint analysis

2022 could have been an even stronger year than it turned out, had it not been for the war in Ukraine and operational issues at most airports as operators struggled to ramp up activity after more than two years of operating at low volumes. Both of these factors constrained capacity and pushed up costs for airlines, with inflated fuel prices and big jumps in landing fees and supplier costs. The underlying strength of demand can be seen in the resilience of volumes in the face of the resulting large hike in ticket prices. In the third quarter of 2022, IAG’s average yield per RPK was 22% higher than in the same quarter of 2019 and their results were not atypical.

I was less confident about the speed and extent of the recovery in business travel. I thought that the doomsters who were predicting that business travel volumes would never recover to more than half of pre-pandemic volumes would be proven wrong. But I also thought that predictions from major airlines for a recovery to 85% of 2019 levels were a bit optimistic, at least in 2022. It was certainly a slow start to the year, but by September major airlines in Europe were reporting business travel volumes of 75-80% of 2019 levels and were forecasting further improvements. So maybe the magic 85% was achieved by the end of the year. We’ll find out when airlines report their results for the final quarter of 2022.

Airline balance sheets

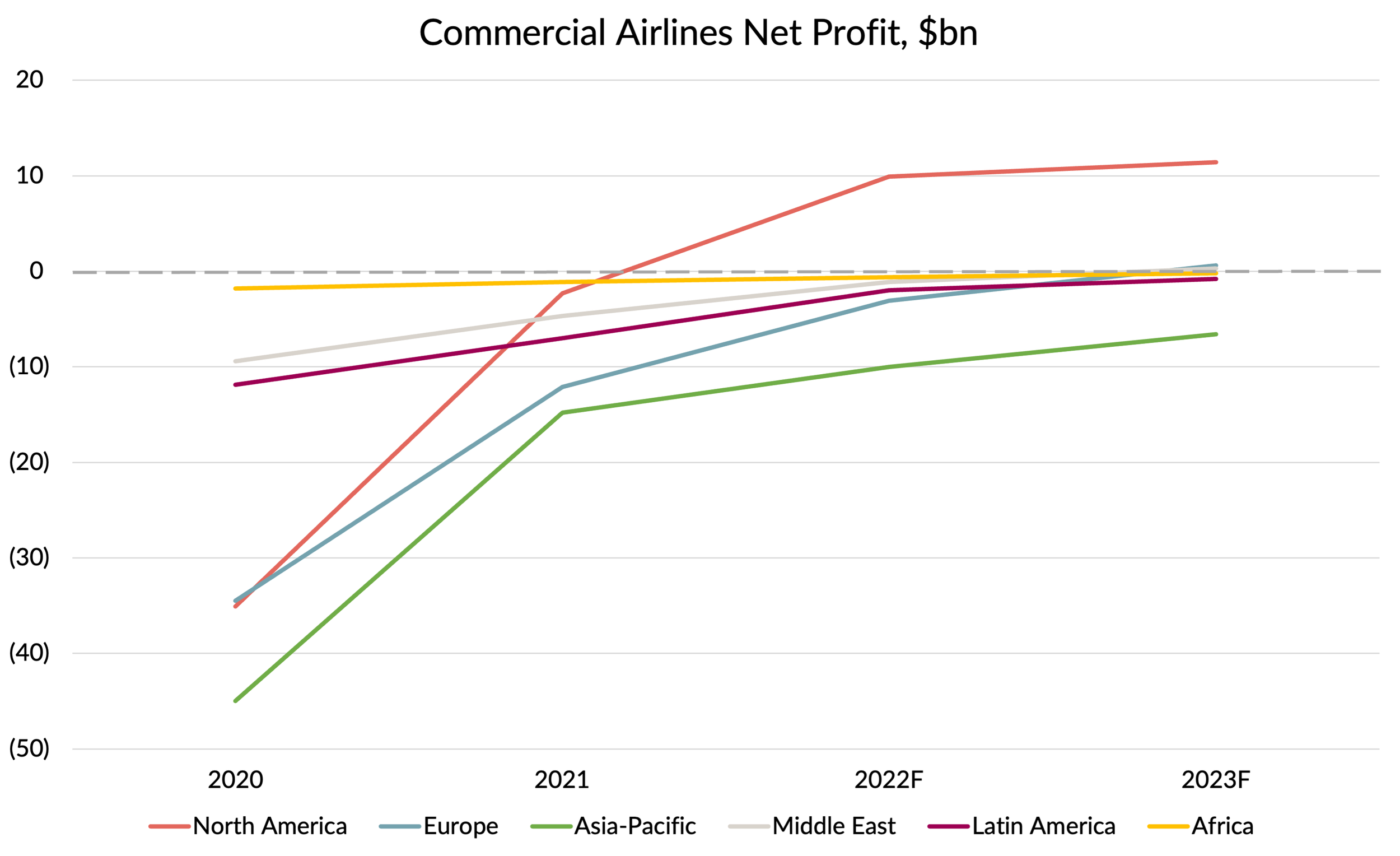

This time last year, I made the observation that it would take years to pay back the $100 billion or so of debt taken on during the pandemic, even if the industry quickly got back to pre-COVID levels of profitability. At the time, IATA were forecasting industry losses for 2020 and 2021 combined would reach $190 billion, with a further $12 billion of losses expected in 2022.

2021 didn’t turn out to be quite as bad as forecast by IATA, with the industry losing “only” $180 billion over the two years of the pandemic. The forecast for 2022 has also improved a bit, to a global loss of $7 billion. But IATA is forecasting that 2023 will not be much better, with only the North American airlines expected to report meaningful profits as a regional group. However, even North American operating margins are only expected to reach 3%.

Asia-Pacific airlines are forecast to continue to lose significant amounts of money, thanks to the slower pace of recovery from the pandemic. Other regions are forecast to be operating at around breakeven - a big improvement on 2020 and 2021, but far from sufficient to restore balance sheets ravaged by the pandemic or finance investment going forward.

Source: IATA

For most of the year at least, private debt markets were open to most airlines and so we have not seen many failures or additional government bailouts. But neither have we seen any real recovery in airline share prices, which might have led to equity capital issuance. The war in Ukraine, slower growth / recessions in major markets, labour disputes and the impact of rising interest rates have all made for an unfavourable backdrop for investor sentiment about the industry, regardless of the recovery in profitability achieved in the year.

Peering into 2023

I’ve written a few of these “predictions for next year” articles now and looked back on them a year later. Even when my predictions have held up fairly well, in every case there have been some big disasters which struck during the year which I didn’t include in my predictions. In 2021, it was the rise of the variants and the onerous travel testing regimes that would be introduced. In 2022, it was the scale of the operational challenges at European airports in the summer and the war in Ukraine, with its associated economic and operational knock-on effects. So this year, I’ve given a bit more thought to the list of things that might go wrong and done an “airline disaster” bingo card.

All of these seem quite likely to impact the industry to some extent or other in 2023, as indeed many did in 2022. I’ll comment on a few of the more interesting ones.

COVID

2023 could be the year which sees the whole world finally “move on” from COVID in the way that much of the Western world did during 2022. That’s not to say that the virus will have gone away, or that new variants won’t continue to emerge. It is likely that we’ll continue to see sporadic reintroductions of testing requirements, as we saw recently in response the huge rise in cases in China. But I think that it is unlikely that we’ll see large scale travel restrictions being reintroduced, now that they have all pretty much been lifted.

The main risk of that changing would be if a variant of COVID or a new virus emerged which was much more deadly. I’d like to think that the world’s response would be more coordinated and better managed “next time round”, but I see no evidence that this would be the case. Global supply chains will continue to face disruption going into 2023 due to the China “exit wave” as they finally relax restrictions.

Ukraine

When it comes to the war in Ukraine, it is hard to be too optimistic. From the perspective of those who, like me, want to see Russia driven out of all illegally occupied Ukrainian territory, the best case scenario is that this could happen during 2023. Such a scenario could see the fall of Putin and we’d all like to think that whatever system of government replaced him would be closer to Western ideals of democracy, economic liberalisation, respect for human rights, the territorial boundaries of its neighbours and the rule of international law. From what I’ve seen and read, that doesn’t seem at all probable.

Whether Putin hangs on or is replaced by somebody as bad or worse, I struggle to see how relations between Russia and the West get repaired or sanctions get lifted any time soon even if Ukraine “wins” on the battlefield. The same would of course be the case if Ukraine is less successful and the war grinds on with little progress made, or if Russia manages to grab more territory. The prospects for a peace deal in 2023 which would be acceptable to both sides seem virtually non-existent to me.

When it comes to the implications of the war for the global economic environment and energy markets, the “status quo” sadly seems to be close to a best case scenario in the next year. It is easy to see how things could deteriorate if Russia starts winning on the battle-field, or loses badly and collapses into chaos. The risks of escalation or conflicts breaking out in other geographies are also easy to see. There are plenty of other border disputes in the world and no shortage of aggressive countries who might seek to take advantage of the resources and attention of Russia and the West being focused on Ukraine.

Operational challenges

I’m a bit more optimistic when it comes to operational challenges at airports. Twelve months is a long time to sort our resourcing issues and the level of uncertainty about demand is lower for 2023 than it was for 2022, so I would assume suppliers will do a much better job next year.

I’m more worried about Air Traffic Control in Europe. Airlines are planning to operate more flights in 2023 than they did in 2022 and the total demand on the system will not be dissimilar to 2019. The system was failing badly back then and the constraints of avoiding Ukrainian and Russian airspace will have made it worse. As far as I can see, not much progress if any has been made in improving efficiency or capacity, so I expect something of a train smash.

Labour shortages and disputes

I think this will continue to be a major issue in 2023, as it has been in 2022. As I’ve already said, it will be much easier to plan required resourcing levels for 2023 than it was in 2022 and the level of risk in making commitments to hire and train people is therefore much lower. Airlines and their suppliers will not want to repeat the mistakes of the last year. So the main risk of shortages should be for “difficult to train” roles. From what I’ve seen, I don’t think most airlines will have issues with pilot shortages. In most cases, deals were done to avoid laying off pilots during the pandemic, achieving savings through temporary pay cuts. But as flight volumes get back to pre-pandemic levels over the next year or two, this will start to become a bigger issue. Engineering and maintenance staff will probably be a bigger problem. The lead-times to train engineers are long and they are less geographically mobile than pilots. With less industrial clout than their better paid colleagues, more of them will have been laid off during the pandemic or taken early retirement.

However, the bigger issue here will be over pay disputes. Airline employees were generally forced to take pay cuts during the pandemic. They can see flight and passenger numbers recovering and, like everyone else, face rising costs due to energy bills and general inflation. It is understandable that they want to see pay restored, uplifted for inflation and will maybe even be seeking to recover their foregone pay. The issue of course is that whilst passenger volumes and revenues are recovering to 2019 levels, fuel and other costs have risen for airlines. As we have seen, profitability is not back to sustainable levels in the industry. There is a mountain of debt that needs to be repaid too. Expect lots of disputes and challenges in 2023.

Sustainability

When it comes to the bundle of issues relating to the environment, I think 2023 will be a year when most airlines start getting serious about the issue. Some have been doing so for a while, but many have focused on publicity stunts (“our first 100% SAF powered flight”) and rebadging aircraft investments which in reality were made in pursuit of growth and fuel cost savings. Supply of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (“SAF”) continues to fall far short of meeting the industry’s stated ambitions. Airlines, airports and fuel suppliers need to start planning for, investing in and reporting on a meaningful scaling up of the production and use of SAF. Governments need to do their part to help, rather than just issuing mandates and applying “the stick”. There is a long road ahead.

Exchange rates, fuel and interest rates

Currency headwinds were a significant issue for airlines not based in the USA in 2022, due to the strength of the dollar. Airlines with significant revenues in dollars or other strong currencies were better protected, but still not immune from the pressures. 2023 may offer some relief. It is hard to see the dollar getting even stronger than it already is and the Euro has already recovered from its September lows.

Fuel prices have fallen from the peaks reached in mid 2022. Forward prices for the second quarter of 2023 are currently around $890 per metric tonne, considerably down in the $1,300 levels seen last summer. Most airlines didn’t pay those inflated rates due to hedging of course, with $800-$900 being a typical hedged rate in summer 2022.

I don’t think that rising interest rates are a major issue for most airlines in the near term. They make heavy use of fixed rate financing, so the risk mainly relates to the cost of new financing deals. Having said that, rising interest rates do increase the difficulty of justifying and funding new aircraft investment.

The economic environment and demand

I’ve left until last the question of what demand is going to look like next year. This could perhaps be the area of biggest uncertainty for airlines.

On the plus side, the first quarter of 2022 was badly impacted by omicron related travel restrictions, which should not be repeated in 2023. We also know that passenger volumes were artificially constrained in peak periods this year due to airport resourcing issues. Heathrow estimated that passenger volumes would have been 10% higher if they hadn’t had to impose passenger volume caps on airlines. Business traffic was very depressed through much of 2022 but was recovering by the end of the year. If that recovery is sustained, that will give a significant revenue uplift to 2023 on a “year over year” basis.

But there are downsides to consider too. Many of the biggest aviation markets face slower economic growth or even recession. In a recession, businesses cut back on travel budgets and consumers don’t have the money to travel. If we were starting from a “solid base" in 2022, we’d be forecasting flat or declining passenger volume and revenues.

One of the biggest uncertainties is the question of “pent up demand”. In 2022, many people hadn’t travelled for a couple of years and were desperate to take overseas vacations and to reconnect with friends and family. Does that mean that “underlying demand” was actually lower than actual demand in 2022 and as pent up demand dissipates, volumes will fall away again?

I think the easier question to answer is what will happen to passenger volumes. Airlines have been struggling to get their operations back up and running at “normal levels”. For many airlines with high fixed cost levels, restoring volume is important for getting unit costs back down. Low cost airlines have been attacking them and eroding their market share. They will not want to see that continue. Based on published plans, seat volumes from Europe will be 95% of 2019 levels in 2023 and 15% above 2022 levels. I think those capacity plans are likely to be maintained even if demand softens. If those seats are operated, they will get filled. The only question is at what price?

Assuming fuel prices don’t spike again, there is scope for prices to fall a bit if they need to without hitting margins as the volume recovery gives unit cost benefits throughout the aviation value chain. If business travel continues to recover that will help yields and also support volume in the winter.

What does all this mean for revenue and profit outlook for European carriers?

Looking back at last year’s “predictions for 2022” article, I found that I was a bit lacking in hard numerical forecasts. I’m going to stick my neck out this year with some more specific forecasts for the European industry.

Overall I’d bet on a substantially better Q1 for European airlines against a soft prior year comparator, maybe as much as 30% in volume terms with higher yields. Summer 2023 should be up 10% in volume terms versus 2022, perhaps with some downwards yield pressure.

For the year as a whole, I think European airlines will get back very close to 2019 traffic levels (90-95%), with unit revenues 10-15% better. Whether revenue growth will be enough to offset inflationary pressures in the cost base and fully restore pre-pandemic profitability will of course vary by airline.

IATA thinks that European airlines will only improve operating margins by about 2% in 2023 compared to 2022. That seems overly pessimistic to me. I think a double digit increase to bring profitability back to 2019 levels is quite possible. All that needs is for the kind of performance achieved in Q3 to be replicated on a full year basis.

Of course this more optimistic forecast doesn’t take into account some of the items on my “airline disaster bingo card”. Strikes, killer viruses, financial market meltdowns, volcanoes and nuclear war could all throw things out.

Stay optimistic

Despite all the challenges faced by the industry in 2022 and the usual long list of things that could go wrong next year, it is undoubtedly the case that the industry ended the year in better shape than it started it.

I for one am going to stay optimistic about 2023 and wish you all a Happy New Year.