Can Heathrow reclaim its crown as the biggest airport in Europe?

The November airports stats are in

We’ve now had the November traffic statistics from all three of the biggest European airports. Before the pandemic, Heathrow was the largest airport in Europe, measured by passenger numbers. The 81 million passengers that Heathrow managed to squeeze through its two runways was ahead of arch-rivals Charles de Gaulle and Frankfurt, despite their significantly greater runway capacity.

Source: Published airport statistics, GridPoint analysis.

Since the pandemic hit, Heathrow has been trailing the other two airports, largely due to more onerous travel restrictions and expensive testing requirements in the UK. As these have eased in recent months, Heathrow has been narrowing the gap and in November it managed to creep back ahead of Frankfurt in terms of total passenger numbers.

Source: Published airport statistics, GridPoint analysis.

Seasonal movements make it a little hard to judge the monthly trends. Looking at the performance in terms of passenger volume compared to 2019 shows that November passenger number figures continued to recover at all three airports on a seasonally adjusted basis. But whilst the gap narrowed, Heathrow has continued to show a slower pace of recovery, compared to pre-crisis levels.

Source: Published airport statistics, GridPoint analysis.

The return of North America

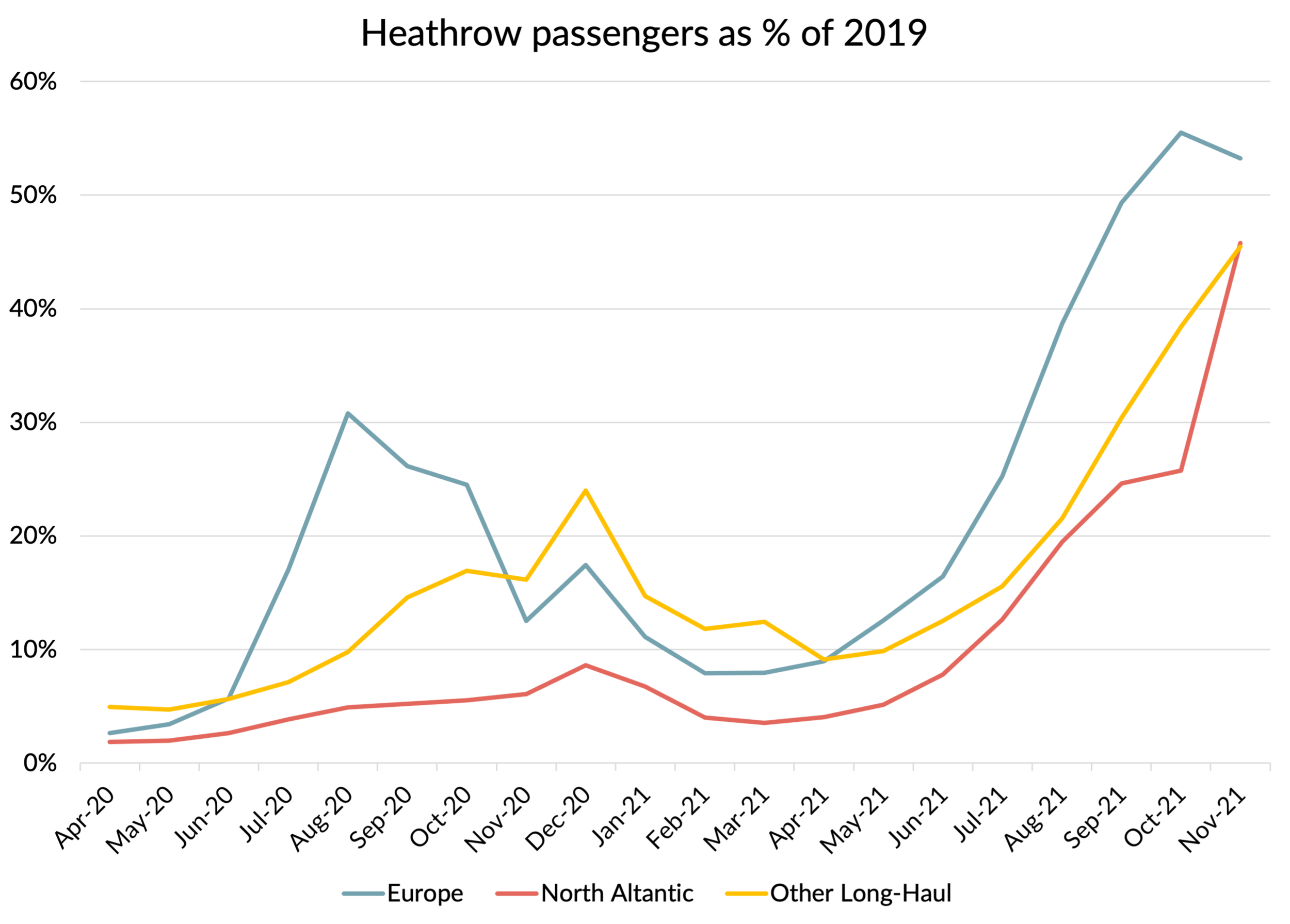

The main reason that Heathrow was number one before the crisis, despite its disadvantage in terms of runway capacity, was the strength of the airport’s long-haul business. Long-haul aircraft almost always have more seats than the aircraft used for short-haul, so carry more passengers per runway slot. But during the pandemic, long-haul markets have been subject to greater travel restrictions and passenger volumes have lagged the recovery in short-haul.

The most striking feature of Heathrow’s November figures was the strong recovery in North Atlantic passenger volumes, following the reopening of the US border to European travellers in early November. The region managed to catch up with other long-haul markets and wasn’t far behind short-haul in terms of progress towards recovering 2019 volumes.

Source: Published airport statistics, GridPoint analysis.

The recovery of the North Atlantic market is particularly important for Heathrow. Whilst overall passenger volumes in 2019 were quite similar between the three airports, the volume to North America was much larger at Heathrow, as show below.

Source: Published airport statistics, GridPoint estimates for CDG figures based on CDG'‘s 93% share of North American seat capacity from Paris in 2019.

Despite this relatively high reliance on the North Atlantic, the region’s direct impact on overall passenger numbers is of course more limited, since even in 2019 the region only accounted for 23% of Heathrow’s overall passenger volume. But many of these passengers were also making onward connections - mainly to Europe. Those connecting passengers get counted twice, so the total percentage of Heathrow’s passengers which were linked to the North Atlantic in 2019 was probably in the 30-35% range.

All three airports have been suffering from the restrictions on travel to the USA. But Heathrow’s recovery has been slower than the other two, as you can see in the next chart. That was probably impacted by the relatively more onerous travel restrictions and testing regimes in place in the UK over much of this period. But Heathrow managed to narrow the gap in November. Travel to North America saw a strong rebound at both Frankfurt and CDG, but it wasn’t as pronounced as at Heathrow.

Source: Published airport statistics, GridPoint analysis. Paris figures are for CDG and ORY combined.

What about Omicron?

I’m sure that the recovery seen in November was on track to continue even more strongly in December. That has probably been blown off course by the Omicron variant, which led to travel restrictions and testing requirements being reintroduced again at short notice. But so far at least, the US has not closed its border again to European travellers, so things are still better than they were before November.

In any event, I expect any Omicron-related restrictions to be quite short-lived. I set out the reasons for this in my last post. For once, it looks like the UK Government agrees with me:

"Very soon, in the days and weeks that lie ahead, if, as I think is likely, we see many more infections and this variant becomes the dominant variant, there will be less need to have any kind of travel restrictions at all." - Sajid Javid , UK Health Minister, December 8, 2021

Indeed, we have already seen the government lifting all the quarantine requirements they imposed on travellers from Africa, although the reintroduction of testing requirements will not be reviewed until January. On the other hand, other countries have been adding restrictions, such as the recent closure of France’s border to non-essential travel by visitors from the UK.

Prospects for 2022 and beyond

Prior to the recent Omicron-related news, many airlines were reporting bookings back to 2019 levels. It is clear that short-term demand has been hit, but if travel restrictions start to get removed again soon, as I think they will, Summer 2022 demand could still remain on track.

In the near term, published capacity from Heathrow shows a continued upward trend. The blue line on the following chart shows how it has tracked so far this year and what is being published by airlines for the next few months. I think that the December capacity number is fairly solid at this point - airlines don’t like to cancel in the last two weeks before departure. But Omicron related cancellations will bring down the capacity operated in January and February. I think that figures for March, April and May are also now likely to be overstated, although that is less certain. The dotted line shows my own guess for how capacity might play out in practice. I’ve also shown the monthly passenger figures. Wherever the red line is below the blue one, that means load factors are below 2019 levels. You can see that airlines have been gradually narrowing the load factor gap during 2021. I’ve hazarded a guess for how passenger numbers might develop over the next few months, reflecting the recovery stalling in the near term but then picking up again from March. But it’s really hard to judge at the moment.

As already mentioned, published seat capacity from Heathrow for Q2 next year is very close to 2019 levels. There are some slot changes like the switch of Alitalia slots to its successor ITA and some carriers like Air New Zealand that expect to be unable to fly. There are a few “intra-group” shuffles amongst the multi-brand airline operators, such as Delta lending slots to Virgin Atlantic to allow it to consolidate its London flying at Heathrow. But overall, S22 published capacity looks largely unchanged from S19. Whether all that capacity gets flown will of course depend on demand, but for an airport like Heathrow where slots are so highly valued, it will also be very significant what slot regulations will apply, something that has still not been decided.

Slot regulations for S22

During the pandemic so far, “use it or lose it” rules have been softened, allowing airlines to cancel more services in response to any demand weakness without putting their slots at risk. Incumbent airlines would like to see that continue for at least another season, arguing that demand remains inherently hard to predict due to constantly changing travel restrictions.

Airports have been pushing to get the normal “use it or lose it” rules reinstated for S22. They know that airlines will probably fly more capacity if that’s the only way they can retain the slots that will be needed when demand recovers. Airports don’t really care if load factors suffer as a result - unlike airlines, airports make money even from empty flights.

One airline, Wizz Air, has been particularly vocal in its support for the reinstatement of the pre-crisis “use-it-or-lose-it” rules. Its motives are different to the airports. As a relatively young airline, it has few valuable slots to protect and as an airline with big growth ambitions, getting access to slots at constrained airports was a big challenge for the company before the pandemic. It is worth remembering that this isn’t really an argument about who gets to use the slots in S22. The way the slot regulation has been relaxed during the pandemic means that to get protection for slots they don’t fly, incumbent airlines have to release them to allow them to be used by others. Wizz will be able to get slots in S22 - but they don’t want to start services they won’t be able to continue.

So the argument is not really about who gets to use scarce slots in S22, it is about who gets to use them in subsequent seasons. Should the airlines who get to use the slots after the pandemic be the carriers that used them before the pandemic, or those who were able to use them during the pandemic?

Your position on that will probably depend on your view on the network airlines, since they are the airlines that tend to have high slot shares at the slot-constrained hub airports, and their core customer sectors have been the most impacted during the pandemic (long-haul and business traffic). The network of long-haul services that is supported by those hub operations will not be replaced by the low-cost, point-to-point oriented airlines that would like to pick up any slots which might get shaken loose. Are the flag carriers vital national assets, or the root of all evil? Are the ultra low-cost airlines like Wizz consumer champions, or are they destroying the planet with their aggressive pricing strategies designed to “stimulate demand”?

For myself, I take a middle view. Europe’s economies need a mix of both business models and travellers are better served where they have a choice. Whatever you think about the slot system, it is hard to say that it has prevented the low-cost sector from growing and prospering. In any event, Heathrow is something of a special case. As one of the highest cost airports in the world, it is hardly a target for carriers like Wizz Air. Airlines with Heathrow slots are not going to just let them lapse. Tougher slot rules at Heathrow would just mean that incumbent airlines will be forced to fly more, at lower load factors.

The EU has now published their slot rules for next summer, with the normal 80/20 rules being modified to a 64/36 rule. The UK is no longer obliged to follow the EU rules, but assuming it adopts something similar, carriers should have a fair bit of headroom to cancel without putting their slots at risk. Whether they use that or not depends on what happens with demand.

Passenger number scenarios for 2022

One of the spats going on between Heathrow airport and the airlines is over charges for the 2022 - 2026 regulatory period. The way the regulatory system works, Heathrow have an interest in low-balling the passenger forecast, since that leads to higher charges. In its submissions to the CAA (the regulator in charge of setting charges), Heathrow have proposed a low case of 15.2 million passengers for 2022, a million passengers below the actual for the first 11 months of 2021. Their mid case forecast is 43.2 million and the high case is 52.8 million, figures which are no doubt intended to support the need for a high allowed rate of return, based on their business having limited upside and lots of downside. Even their upside case at only 65% of 2019 levels looks ultra conservative to me. IATA is forecasting intra-European passengers numbers at 75% of 2019 in 2022, for example.

Airlines have the opposite incentive and they’ve proposed a figure of 72.0 million, 89% of the 2019 figure. That’s possible, of course. But it would require published capacity to hold firm without material cancellations and load factors to get back close to normal levels.

The CAA’s initial proposals are close to Heathrow’s very gloomy outlook, with a mid case of 45.6 million, which seems way too low to me. But if the CAA continues to base its calculations on figures which are close to Heathrow’s pessimistic forecasts, airport charges will go up a lot from levels which are already over 40% higher than other European airports. So this unambitious passenger number forecast might become a self-fulfilling prophesy, with the recovery throttled by higher airport charges.

Will Heathrow get back to number one?

It seems likely that the three airports will trade places on a monthly basis for a while, but a big part of whether Heathrow gets back to number one on a sustainable basis depends on how well it works with its airline customers. It doesn’t bode well that it seems to be pre-occupied with maximising prices for its customers, rather than on driving a volume recovery through a partnership approach.

If Heathrow really cares about getting back to number one, it had better hope that its competitor airports are adopting the same “price maximising” strategy. Neither Aéroports de Paris , who own CDG, or Fraport, who own Frankfurt Airport are known as the most commercial or efficient airport operators in the world. But at the moment, the only crown that I’d be confident Heathrow will retain is its place as the most expensive major airport in Europe.